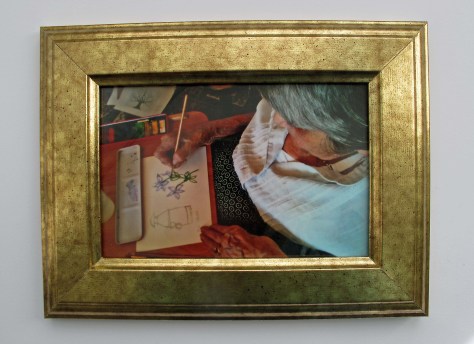

The first series of art workshops, where we have been working with residents from a care home to create new images and objects, each capturing a significant memory, seem to have been very much enjoyed by the participants.

Some of the paintings from the early sessions have been framed and shown at the recent Connected Communities conference in Cardiff.

One resident has a fond and vivid memory of periwinkle flowers which grew profusely in her childhood garden, and so it was this enduring image that she chose to reproduce in both watercolour (above) and scribe into the surface of casting wax (below). The wax was a wholly new material to her, but she was keen to experiment and interested to hear that it could be cast into bronze, by making a rubber mould from her original work.

When I showed D the resulting bronze cast of her artwork, she was visibly delighted, and amazed that she could have produced something that looked, in her words, ‘so expensive’. In bronze, the cherished memory now has a permanence that will last beyond the fleeting moment of remembering. As I was leaving, D made a comment that seemed to support the purpose of the entire project:

‘It’s a good idea this [project], you tell them that. It’s really got me thinking. The trouble is you get so old and you think you’ve forgotten everything, all these things – but you haven’t. The memories just need fishing out.’

Hopefully as a team, through these art workshops and the many other creative approaches, we can continue to assist the residents in ‘fishing out’ their memories, which may otherwise have drifted away.

In the book, Art as Therapy, the authors Alain de Botton and John Armstrong, go some way to echoing D’s comment:

‘We’re bad at remembering things. Our minds are troublingly liable to lose important information, of both a factual and a sensory kind. […] Art helps us to accomplish a task that is of central importance in our lives: to hold on to things we love when they are gone.’

The writers also point out that: ‘Art can be a tool, and we need to focus more clearly on what kind of tool it is – and what good it can do for us’.

The collection of fragmented objects (below) have proved extremely useful and fascinating as a set of tools for evoking memories and stories, functioning as a kind of 3D collage, where each artefact recalls something different for each individual:

In the image above, there are two RFID tags, on either side of the group of objects, and as a team, we are considering methods by which these ‘art tools’ or objects, could be augmented using near-field communication technology, in order to add a layer of story content to each item.

By exploring these digital technology options, we are, to a certain extent, seeking to ‘add value’ to some of the objects with which we are working. This has inevitably led to broader discussions about value, both the inherent and tangible value of collectable family heirlooms for example, as well as the sentimental value often attached to more personal possessions and the memories associated with them.

While prevailing concepts of the word value tend to centre around money and finance, I began to think about the significant absence of currency in the care home environment. Cash is not usually required, as the residents have nothing to spend it on in their immediate everyday surroundings, and cannot easily go out into the community without prior arrangement and support. The lack of monetary exchanges that are so integral to our daily social encounters for the greater part of our lives, are suddenly missing. Paradoxically however, the high and rising cost of care provision needs an increasing volume of financial investment to sustain it.

With money comes agency and choice, and a level of empowerment and confidence widely recognized as important for any individual. Equally, art has been identified as having a capacity for agency in a book called Winter Fires: Art and agency in old age, producedby the London Art in Health Forum and the Baring Foundation:

‘Children and young people want to be thought older than they are because with adulthood comes agency - the ability to act autonomously in the world, to make our own decisions, to pursue our desires, to write our own story. And it is the loss of agency, above all through mental incapacity, that is most feared as old age advances…..

But a capacity to create…is in all human beings, including those who do nothing to develop it after primary school. Art is a capacity for agency that….can flourish, indeed, in old age and help preserve individuality and autonomy to the very end.’

As a result of both art and money being identified means of increasing autonomy, this week I will be facilitating a type of coin-making workshop with the residents from another of the care homes, before we begin to experiment with these unique objects of value in some system of exchange, a kind of micro-currency within the care home environment.

Much like D’s wax cast into bronze, the residents can start by drawing a significant memory or symbol of something important to them, into the surface of a wax hexagonal shape. The smallest ‘coin blank’ starts at similar size to the 5 pence piece, while a much larger hexagon is available for more short-sighted participants or those with dexterity issues.

Next month, in a care home where the majority of residents are suffering from the advanced stages of dementia, we will also begin experimenting with pre-decimal money, in the form of the ‘thrupenny bit’ or threepenny coin. Tim Lloyd-Yeates, Director of Alive! Activities reminded the team that in the midst of memory-loss, the strongest recurring memories are those which we have experienced between the ages of 10 and 30 years old. For most of the care home residents, this would mean vivid recollections of using pre-decimal money.

Alongside these ideas of introducing a micro-currency into the care home environment, this Radio 4 programme explored a really interesting form of alternative currency, applied to care of the elderly in Japan:

The programme summary raises some crucial questions:

The UK, like many countries, faces the problems of an increasingly ageing society. The number of people aged 65 and over is projected to rise by 23% from 10.3 million in 2010 to 16.9 million by 2035. How can we provide and pay for their care?

Japan is at the forefront of the ageing crisis, with the highest proportion of elderly citizens in the world. By 2030, almost a third of the population will be 65 or older. At the same time the overall population is shrinking, leaving fewer young working people to shoulder the burden of paying for care for the elderly.

One creative response to this challenge at local level has been a cash-less system of time-banking. Under the fureai kippu system, individuals donate time to looking after the elderly, and earn credits which they can - in theory at least - “cash in” later for their own care, or transfer to elderly relatives in other parts of the country.

Could something similar work here, or do we have very different attitudes to community and volunteering? Who would benefit from such a cash-less scheme, and who might lose out? Could it be scaled up to meet the escalating needs of a growing elderly population?

Ultimately, whether it is time or money, art objects or memories that we will be exchanging in the care home of the future, new ways of thinking about ageing are vital now, in addition to providing a sustainable and personalised means of support for everyone.