Recently, we held a group session with residents that focused on the theme of favourite walks. For some of the older people we are working with, access to the outdoors represents a physical challenge or a rare treat, while the residents of this particular assisted living location generally enjoy a much greater level of independence and freedom to go outside.

The participants in this lively group discussion came prepared with a significant walk in mind from any point in their lives, and seemed to relish sharing their experiences about a walk, or pattern of walks, that had memorable meaning. One gentleman remembered the familiarity of his walk to infant school, made suddenly dramatic one day in 1927, when a bi-plane landed in a field next to the primary school. This was the first aeroplane he had ever seen. One lady took the opportunity to advertise a sponsored walk she had planned for the very next day, to raise money in aid of the resident’s activity fund. She was hoping to make two circuits around the building where the group live, but promised that if she could get a skateboard, she would be able to make it three! There were reminiscences about walks in Blaise Castle and the Hamlet, that seemed ‘like walking in a fairyland’, while others fondly recalled walks with a husband or wife amongst snowdrops or bluebells in the Springtime. For another lady, walking on land was significant in itself, as she and her family had lived on board a boat and her daughter had learnt to walk while they were at sea.

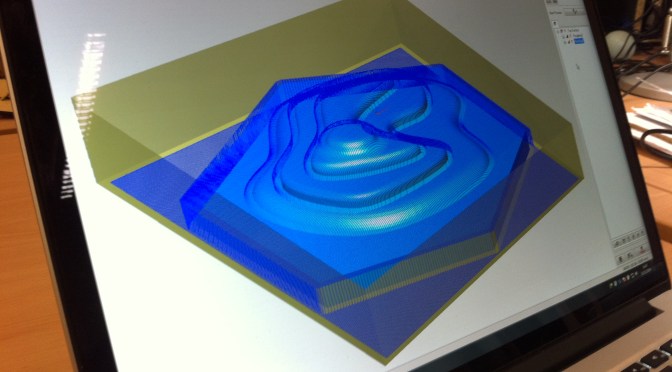

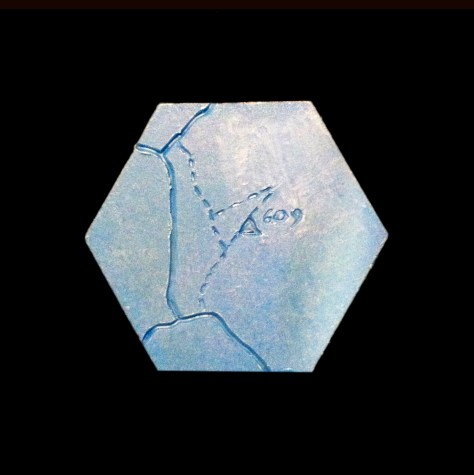

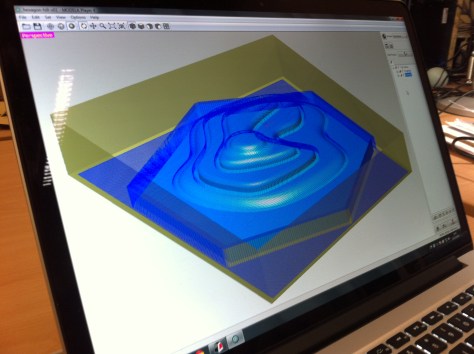

One of the outcomes of this session, exploring favourite walks and nearby locations, was the desire to revisit some of these places in real life, in order to re-experience them and have the chance of uncovering more distant memories. Adopting the more curatorial approach on offer (see post re TopoTiles), the group decided that they would enjoy visiting the MShed, a local museum about Bristol, its places, people and their stories, which effectively seemed to represent several of the locations that they had been discussing.

As a result, one blustery cold morning, we gathered into a minibus and travelled to Bristol’s harbourside to explore the MShed, and the many intriguing objects on display there.

In addition to the curated exhibitions that stretched across three floors of the museum and were complemented by wintery harbourside views, the residents particularly enjoyed a guided tour of the museum’s stores, known as the LShed.

Behind-the-scenes, in a dimly-lit warehouse, these uncurated and large-scale artefacts seemed all the more enticing somehow, stacked on shelving, without labels or glass cases, or peeking out from underneath plastic sheeting and behind cupboard doors.

In this unordered space, it felt as if there was more to discover in a serendipitous way, and this led to a greater number of memories being evoked for the residents, in response to the historic objects they observed among the aisles of storage.

The spontaneous discovery and revelation of items within the LShed collections seemed to vividly reflect the way in which we store our memories, as well as the manner in which we tend to recall them. Jumbled and disorderly, sometimes hidden from view, our past is usually recollected in a non-linear fashion, leaping from one event to another, bounding across years and back again.

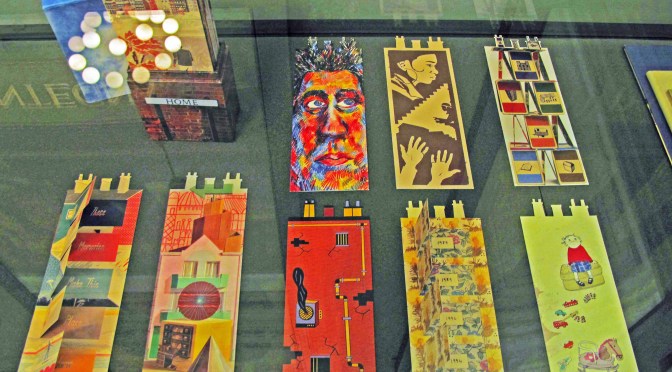

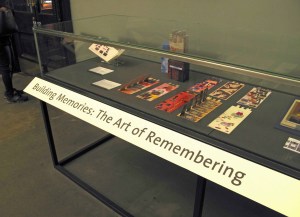

The visit to the MShed and LShed, and the stories which the day evoked, were captured through a series of photographic images and sound recordings. Initially, the residents have chosen to use this material in a temporary exhibition in one of the communal living areas at their home:

Five images were selected from the museum visit, with accompanying sound recordings that related to the objects in the photos.

Using three push-button sound systems already available in the foyer, we recorded short excerpts of narrative, into each of the three units:

Here is an example, featuring one of the LShed mangles:

The residents now have further plans to share different aspects of their museum visit, including a slideshow for friends and neighbours (to be held later this month) and the suggestion of a ‘virtual museum’ to be installed at the home. This would involve using some of the images of the objects in store, within the Oculus Rift virtual reality headset, so that those residents who are physically unable to travel to the museum itself, might be able to enjoy a similar, serendipitous discovery of the LShed and reminisce around the artefacts for themselves.